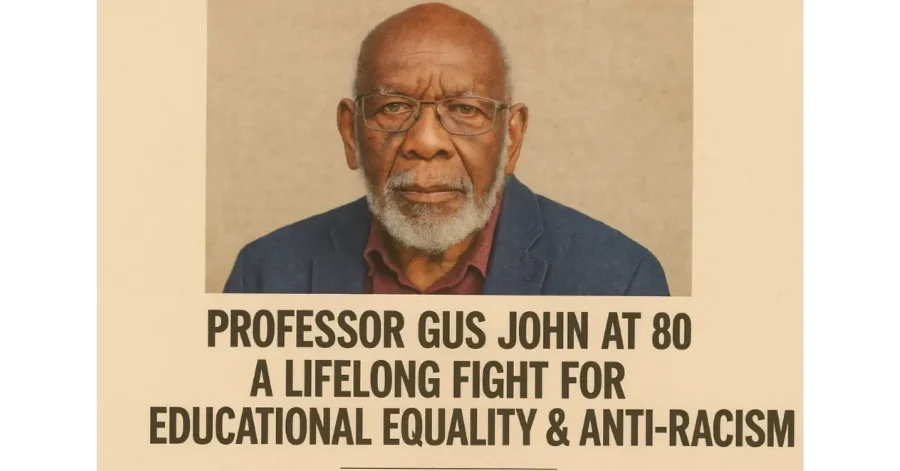

Professor Gus John at 80: A Lifelong Fight for Educational Equality & Anti-Racism

At 80 years old, Professor Gus John remains as passionate and vocal as ever in his fight against systemic racism and educational inequality. From his humble beginnings in a two-room shack in Concord, Grenada, to becoming the UK’s first Black Director of Education, his journey spans six decades of relentless activism, scholarship, and community organizing. As one of Britain’s most respected voices on racial justice, Gus John has dedicated his life to challenging the structures that perpetuate inequality, particularly within the education system, where Black children continue to face disproportionate barriers to success.

Speaking exclusively to The Voice as he marked his 80th birthday in March 2025, Professor John reflected on his remarkable journey while issuing a clarion call for renewed action against the persistent inequalities that plague British society. His story is not just one of personal achievement, but a testament to the power of collective action and the enduring importance of education as a tool for liberation.

Early Years: From Grenada to Oxford’s Hallowed Halls

The Making of an Activist

Born on March 11, 1945, in the village of Concord in Grenada’s parish of St John’s, Gus John’s early life was shaped by the realities of colonial rule and the aspirations of peasant farmers who understood the transformative power of education. At 12, he won a scholarship to the prestigious Presentation Boys College in St George’s, and at 17, he began theological studies in Trinidad before transferring to Oxford University at 19.

It was at Oxford in the mid-1960s that John first encountered the brutal realities of British racism. As Chair of the Education Subcommittee of the Oxford Committee for Racial Integration (OCRI), he witnessed firsthand how Caribbean students and workers faced systematic discrimination in housing and employment. These experiences would shape his lifelong commitment to anti-racism activism and his understanding that education must be coupled with political action to achieve meaningful change.

Pioneering the Black Supplementary Schools Movement

In 1966, while still a student at Oxford, Gus John co-founded the first Black supplementary school in Oxford, followed by another in Birmingham’s Handsworth area in 1968. These Saturday schools were revolutionary responses to the systematic educational neglect and cultural violence that Black children experienced in mainstream British schools.

The Black supplementary schools in the UK represented more than just academic support; they were spaces of cultural affirmation, political education, and community building. As Professor John explained in his recent interview:

“When I started the first such school in Oxford in 1966, we focused on building children’s self-esteem. We gave them a sense of belonging and helped them build a positive and liberated mindset so they could cope with being berated in mainstream schools.”

These schools addressed multiple interconnected issues: the disproportionate placement of Black children in schools for the “educationally subnormal,” the practice of busing Black children away from their neighborhood schools, and the systematic undermining of Black children’s confidence and academic potential.

Confronting Systemic Racism in UK Education: The 1970s Crisis

The Educational Subnormal Scandal

One of the most damaging practices that Gus John fought against was the systematic mislabeling of Black children as “educationally subnormal” (ESN). In the 1960s and 1970s, hundreds of Black children were wrongly placed in special schools, not because of genuine learning disabilities, but because of racist assumptions about their intellectual capacity.

Professor John’s groundbreaking 1971 work, “How the West Indian Child is Made Educationally Subnormal in the British School System,” exposed this scandal and provided crucial evidence for what would later be understood as institutional racism.

This work earned him the Martin Luther King Memorial Prize in 1971, recognizing its significance in documenting and challenging racist educational practices. The impact extended far beyond academia, sparking community campaigns and policy reforms.

Building a Movement: The Caribbean Teachers Association and Black Parents Movement

The 1960s and 1970s were marked by collective organizing. Alongside supplementary schools, key groups like the Caribbean Teachers Association (1974) and Black Parents Movement (1975) emerged.

These organizations recognized the intersection of racism, poverty, and exclusion and championed fundamental changes in educational systems—not just better teaching methods but dismantling the assumptions that underpinned systemic racism in British schools.

A Groundbreaking Career: Britain’s First Black Director of Education

Breaking Barriers in Educational Leadership

In 1989, Gus John became Britain’s first Black Director of Education, serving in the London Borough of Hackney. His appointment was both symbolic and practical: it placed an anti-racism activist at the helm of one of London’s most diverse boroughs.

During his tenure, Professor John emphasized high expectations, community engagement, and culturally responsive education.

Academic Contributions and International Recognition

Professor John has held academic posts at the University of Bradford, Strathclyde, and UCL Institute of Education. In 2016, he was named one of the 30 most influential Global African Diaspora leaders and joined the African Union’s Technical Committee of Experts to help develop the “Sixth Region” concept for African diaspora communities.

Contemporary Challenges: The Persistence of Educational Inequality

Modern Manifestations of Historic Problems

Despite years of activism, Professor John insists that Black children in 2025 face many of the same barriers seen in the 1960s.

Black Caribbean boys continue to be excluded at nearly four times the rate of their white peers. The “school-to-prison pipeline” remains a grim reality.

The Child Q Case and Continuing Discrimination

The strip-search of a 15-year-old Black girl, known as Child Q, highlights the ongoing “adultification” of Black children. Professor John likens this to the dehumanizing practices of the ESN era—rooted in the same institutional racism.

The Windrush Scandal: A Contemporary Manifestation of Historic Racism

Connecting Past and Present

Professor John’s critique of the Windrush Lessons Learned Review framed the scandal as part of a larger continuum of systemic racism—from stop-and-search to hostile environment policies.

His ability to “join the dots” demonstrates the historical continuity of anti-Black state violence in the UK.

Defending Black Women in the Public Sphere

Professor John has defended public figures like Diane Abbott, highlighting how attacks on prominent Black women are attacks on the broader Black community. His stance underlines the importance of collective protection and unity.

Educational Philosophy: Decolonizing Minds and Building Community

The Importance of Cultural Education

Professor John’s Saturday schools pioneered what is now widely called decolonizing the curriculum. He championed teaching African and Caribbean history as foundational—not supplementary—education.

Empowering Black Youth UK: Beyond Individual Achievement

He advocates for education that creates engaged citizens, not just successful individuals. This includes political literacy, cultural grounding, and a commitment to collective advancement.

Contemporary Activism: Continuing the Fight at 80

Calling for Revival of the Supplementary Schools Movement

Professor John urges a return to community-led supplementary schools—ones that support children psychologically, culturally, and academically in ways mainstream systems still fail to do.

Parliamentary Engagement and Policy Advocacy

Despite his critiques of institutional racism, Professor John remains engaged in policymaking, participating in parliamentary discussions to shape education reform from within.

International Perspectives: Connecting Local and Global Struggles

Pan-African Solidarity and Development

His involvement with African development, especially in Nigeria and with the African Union, reflects his belief that British racism is part of a global structure of oppression.

Climate Justice and Reparations

In recent years, he has expanded his activism to include climate justice and reparations, highlighting how colonial histories shape global climate vulnerability and economic injustice.

Personal Reflections: Faith, Family, and Future

Maintaining Hope Through Struggle

Rooted in Christian faith, Professor John’s optimism has helped him persist through decades of activism. He sees hope in grassroots movements and young people.

The Importance of Intergenerational Connection

He continues to mentor and work with younger activists, understanding that intergenerational knowledge-sharing is essential to movement sustainability.

Recognition and Legacy: Honors and Continuing Impact

Academic Recognition and Public Honors

John has received honorary degrees from De Montfort University, University of London, Birmingham City University, and University of West London. Notably, he declined a CBE in 1999, consistent with his anti-imperialist principles.

The Gus John Legacy in Contemporary Movements

Today’s education justice campaigns often build on Professor John’s methods. His legacy lives on in their organizing, their curriculum work, and their political frameworks.

Looking Forward: Challenges and Opportunities for the Next Generation

Persistent Challenges in British Education

Exclusions, curriculum bias, and low expectations continue. The rise of far-right ideologies adds urgency to his call for renewed resistance.

The Need for Sustained Commitment

Professor John reminds us that structural change takes decades. His example of consistent activism is a roadmap for new generations.

Conclusion: An Unfinished Revolution

At 80, Professor Gus John continues to fight for racial and educational justice. His life stands as a beacon for how activism, scholarship, and community organizing can intersect for lasting change.