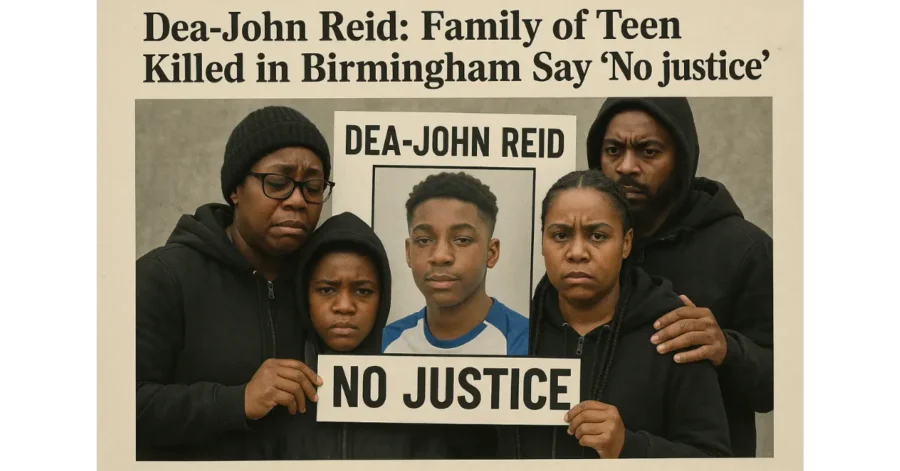

Dea-John Reid: Family of Teen Killed in Birmingham Say ‘No Justice’

On 31 May 2021, 14-year-old Dea-John Reid left home in the Kingstanding district of Birmingham to play football and never returned. CCTV and witness reports show a group of five white men and boys chasing him down College Road, shouting racial slurs like the “N-word” and “Black bastard,” before one of them fatally stabbed him in the chest. Dea-John collapsed and died at the scene from the single knife wound to his heart. His death was immediately ruled a homicide, shocking the local community.

At a vigil on the anniversary of his killing, Reid’s family and supporters gathered at the very spot on College Road where he was stabbed. People gathered in Kingstanding, Birmingham, for a vigil three years after 14-year-old Dea-John Reid was killed, highlighting the ongoing quest for justice. The crowd held up signs saying “Justice for Dea-John Reid”, reflecting the demands of the Justice 4 Dea-John campaign. This grassroots movement, led by community leaders and the Reid family, is calling for legal reforms such as more ethnically diverse juries and stronger laws against racial hate crimes.

The Birmingham Stabbing in 2021: What Happened

Dea-John Reid’s killing unfolded in broad daylight on a busy road. According to police and trial evidence, earlier that day a minor argument had erupted – one boy in Reid’s group was accused of trying to steal a bag from one of the attackers. Minutes later, witnesses saw Dea-John running for his life as one adult and two teenagers emerged from a car and joined the chase with tools and weapons. CCTV from the scene shows a teenager wearing a balaclava and gloves catching up to Dea-John and plunging a large kitchen knife into his chest. Some of the group carried a wrench and another knife. Immediately after the attack, Dea-John was left bleeding on the road. Emergency services arrived quickly, but he was already dead.

The West Midlands Police treated the case as murder. Six suspects – four men in their 30s and two teenage boys (including the killer) – were arrested on suspicion of murder. The police noted that racial abuse had been directed at Dea-John during the earlier confrontation, including evidence one attacker shouted “we’re going to get the Black bastard.” Initially, police said they were not sure if the crime was racially motivated. Local campaigners, however, demanded a thorough investigation of racial motive. The police ultimately referred the case to the Independent Office for Police Conduct to review how they had handled earlier contacts with the victim.

Trial and Verdict: Manslaughter, Not Murder

In spring 2022, the case went to Birmingham Crown Court. A 15-year-old boy (whose identity is protected by law) was tried as the main attacker. The evidence included the chilling CCTV of the chase and stabbing, as well as witness testimony. Notably, several witnesses described hearing racial slurs from members of the group. Reid’s mother, Joan Morris, told the court she felt her son had been “hunted by a lynch mob”. She compared the scene to a moment in Mississippi Burning, evoking deep horror at the racial overtones of the attack.

Despite this, the jury acquitted the defendants of murder. The 15-year-old was instead found guilty of manslaughter – meaning the court agreed the killing occurred but ruled he had no intent to kill in the strict legal sense. During sentencing, Mr Justice Johnson noted that if the killer had been an adult, the same act “would almost certainly be murder” and carry a life term. Instead, the judge sentenced the teenager to six-and-a-half years in custody. Under UK rules for young offenders, he will serve only half of that time in a secure facility (about three years) before release.

This verdict left Dea-John’s family stunned. In court Joan Morris wept: “If that is manslaughter, what is a murder?” she asked. Family spokesman Bishop Desmond Jaddoo called the outcome “quite farcical” given the evidence. Activists note that all the defendants and jurors were white, while the victim was Black – a striking racial imbalance in Birmingham’s ethnically diverse community. The family believes these facts influenced the jury’s decision. Joan Morris said flatly, “I don’t know what the jury were looking at… For that jury to say this is manslaughter. They showed me racism right there.”.

- Key Trial Facts: Dea-John was chased and stabbed to death by a group of five (two adults, three teens). One 15-year-old attacker was convicted of manslaughter. Four co-accused (two adults, two youths) were acquitted of murder. The killer’s 6.5-year sentence translates to only about 3 years in youth detention. The judge lamented that an adult doing the same act would face life in prison.

Murder vs. Manslaughter – UK Law Explained

In England and Wales, murder is the most serious charge and requires proof that the killer intended to cause death or really serious harm. It carries a mandatory life sentence. In contrast, manslaughter covers killings where intent is lacking or there are mitigating factors (like a loss of control or diminished responsibility). The penalty for manslaughter can also be up to life, but judges have more discretion and sentences are typically lower. In this case, the jury must have concluded the 15-year-old lacked the specific intent for murder (perhaps thinking it was an unplanned act of violence). The result – a manslaughter verdict – has sparked debate. As one legal expert put it, many feel the system turned a “very violent attack” into a lesser offense without considering the racial element.

Racial Bias and Jury Diversity

The Reid case has raised uncomfortable questions about racial bias in the UK jury system. Jury members are selected randomly from the local electoral register, but many argue this process often fails to produce a panel reflective of the community’s ethnic mix. In Birmingham, for example, about one-third of residents are Black, Asian or from other minorities, yet the jury in this case had 11 White jurors and only one South Asian. Dea-John’s mother believes the all-white jury did not grasp the seriousness of the racist abuse her son suffered. Bishop Jaddoo noted dryly at the march, “We had a jury of eleven white members and all of the defendants were white while the victim was Black… You ask yourself: why?”.

Public opinion appears to side with the family. A University of Birmingham survey found 61% of respondents agreed more diverse juries are fairer, yet there are currently no legal rules requiring ethnic balance on panels. Campaigners say this must change. They note that the jury’s verdict felt like a “second violent blow” to the Reid family. The Justice 4 Dea-John Reid (J4DJR) campaign, led by Dr Bishop Desmond Jaddoo and family members, is advocating legal reforms. They want measures ensuring juries reflect local communities. For example, they propose allowing limited questioning of jury demographics or other steps to prevent an all-white panel in a multi-racial city.

The Justice 4 Dea-John Campaign and March for Change

Dea-John’s tragic death prompted an outpouring of grief and anger. In the weeks after the trial, family and supporters organized marches and rallies. On 9 July 2022, hundreds of demonstrators marched through Kingstanding chanting “No justice, no peace!”. They wore purple – Dea-John’s favorite color – and carried placards demanding “Justice 4 Dea-John”. His mother Joan Morris joined the march, often too emotional to speak. Bishop Jaddoo told the crowd: “We marched through Kingstanding because we had to make a strong statement… Some may ask why we’re marching. Well, there’s been no justice for Dea-John or his family.”

The campaign’s key demands include:

- Diverse Juries: End all-white jury panels. Ensure future juries in diverse areas mirror the population. In Jaddoo’s words: “The city’s criminal justice system must reflect Birmingham’s mix of communities”.

- New Civil Rights Laws: Introduce a Race Relations/Civil Rights Act to tackle racist violence and hate speech. Activists say current hate-crime laws are insufficient. They want explicit legislation to punish racist attacks on civilians and protect victims like Dea-John. Bishop Jaddoo told The Independent that the group is “lobbying the government to act”, pushing both jury reform and new civil-rights legislation.

- Review Hate Crime Prosecution: Highlighting the issue of hate crimes, the campaign urges clearer laws so that evidence of racist motive (like the slurs shouted at Dea-John) is fully considered. Right now, hate-crime sentencing enhancements under law (e.g. Section 66 of the Sentencing Act 2020) only apply when a crime is proven to be motivated by hatred. In Dea-John’s case, the CPS later noted no hate crime conviction was possible because the convicted youth didn’t utter those slurs; only other attackers did. Activists argue this loophole must close.

Mrs. Morris and campaigners are clear their fight goes beyond one verdict. As she put it: “My son didn’t get any justice, and this campaign is shining a light so we can get equal juries and that you won’t be judged for the colour of your skin.”. They are pressing the UK government to take notice. Supporters have launched petitions (such as on Change.org) and even held a national march in July 2022. Public figures like Birmingham’s bishop Desmond Jaddoo have spoken out about other cases, comparing how Black defendants often get harsher outcomes. For instance, Jaddoo pointed to a Manchester case where four Black teens were jailed for a group attack, observing: “no one lost their life… but they all got found guilty. This [Dea-John’s case] happened in broad daylight.”

Hate Crime and Legal Context in the UK

Under UK law, crimes motivated by race, religion or other protected traits are classified as hate crimes. In England and Wales, the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) guidance states that after a conviction, courts can increase the sentence if hostility is proven. For example, Section 66 of the Sentencing Act 2020 allows uplifted sentences for hate motivation. However, to do this, a defendant must be convicted of the hate element. The CPS made clear that in Reid’s case, the convicted teen “did not use any racist comments towards Dea-John”, so legally no hate crime conviction was possible. The other attackers were acquitted, meaning the judge could not factor in the racist abuse they had uttered. A CPS spokesperson explained: “We take hate crime extremely seriously but can only apply for a sentence to be increased where there has been a hate crime conviction.” In other words, even though witnesses heard racial slurs, there was “no evidence that the attack was motivated by racial hatred” under the law.

The disparity between the brutal facts and the legal outcome has prompted calls for legal reform. Some experts note that UK hate crime law relies on case-by-case flags and CPS decisions, rather than automatic consideration of slurs heard at the scene. Campaigners want clearer rights for victims. They argue that if racism is part of an attack, courts should be allowed to reflect that in sentencing even if it is not a separate charge. On a broader scale, government data show that racially motivated crimes are far from rare: in 2022 there were over 109,000 race hate crimes recorded in England and Wales (about 70% of all hate crimes). Many communities feel convictions and sentences do not match those numbers.

Conclusion: Seeking Justice and Change

The killing of Dea-John Reid and its aftermath remain painful reminders of tensions around race and justice in the UK. His parents and community have vowed to keep fighting. As Dea-John’s brother Kirk Reid said, he remembers his brother as “talented and gifted,” a football-loving boy with big dreams. They want the world to remember Dea-John for his life and potential, not just how he died. Joan Morris insists that even if no one can go back, “at least his name would live on” through change.

For readers following this case, the campaign asks: look beyond the verdict. What do families like the Reids need to see? Better representation on juries? Changes in law so that racist violence is recognized as such? By learning about their struggle – through national marches, petitions, and news like this – we all can help apply pressure for reform. The story of Dea-John Reid has become more than a court case; it’s now a rallying cry for racial justice in Britain.